Critical Minerals in Africa The Definitive Guide for 2025 | OFei Lens

Explore what critical minerals are, where they are found in Africa, and why they matter for the world’s green and digital transition. A clear guide to the countries shaping the future of energy and technology.

CHINA & AFRICA

Harriet Comley

11/10/20254 min read

In the twentieth century, the world was shaped by oil. In the twenty first, it will be shaped by minerals.

As global demand for electric vehicles, renewable energy, and digital technology accelerates, a new category of resources has become the foundation of modern power: critical minerals. These are the metals that make the world’s batteries, magnets, chips, and circuits function, and Africa holds more of them than almost any other continent on Earth.

What Are Critical Minerals

Critical minerals are the essential raw materials needed for high technology and clean energy industries. They include lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, graphite, and rare earth elements as well as the so called three Ts: tin, tungsten, and tantalum.

These minerals are the backbone of modern technology.

Lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, graphite form the core of electric vehicle batteries.

Copper powers wind turbines, grids, and data centres.

Rare earths are essential for everything from smartphones to fighter jets.

Tin, tungsten, and tantalum are found in circuit boards and electronics.

Without them, the world’s green and digital transition would come to a halt.

Where They Are in Africa

Africa’s mineral map is vast and varied. The continent supplies many of the minerals considered strategic by the United States, the European Union, and China.

Cobalt: The Democratic Republic of Congo produces over seventy percent of the world’s supply. Zambia follows closely with integrated copper and cobalt operations.

Lithium: Zimbabwe, Namibia, Ghana, and Mali are leading the new lithium rush. Zimbabwe’s Bikita and Arcadia mines are already among the world’s fastest growing producers.

Nickel: Madagascar, Botswana, and South Africa hold significant reserves.

Manganese: South Africa, Gabon, and Ghana remain major global suppliers.

Copper: The Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia dominate, with Botswana and Namibia emerging.

Graphite: Mozambique and Madagascar are global leaders in large flake graphite, while Tanzania is rising fast.

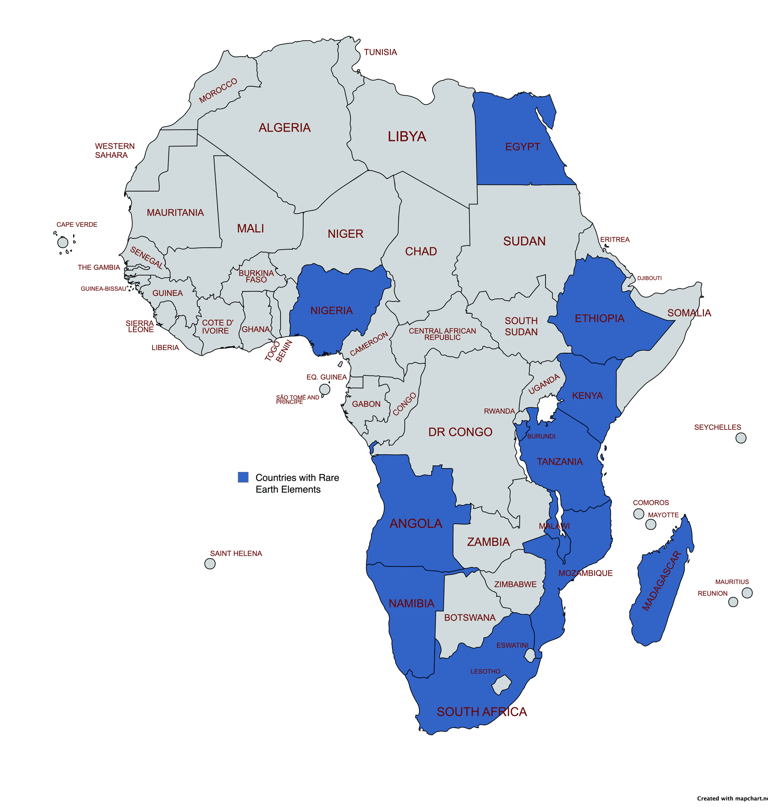

Rare Earth Elements: South Africa, Namibia, Tanzania, and Madagascar are developing world class projects.

Tin, Tungsten, and Tantalum: Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo lead, supported by improved traceability and conflict free mining initiatives.

Uranium: Namibia and Niger continue to supply world markets.

Bauxite: Guinea remains the continent’s giant, with Ghana as a smaller but stable producer.

These resources are not evenly distributed, but together they position Africa as the single most important region in the world for the clean energy economy.

China’s Long Game

China recognised this opportunity two decades ago. While Western economies were focused elsewhere, Beijing quietly built a network of mines, smelters, and refineries across Africa.

Companies such as CMOC in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sinomine in Zimbabwe, and Chalco in Guinea now anchor China’s mineral supply chain.

But China’s real advantage is not in mining, it is in processing. Even when African minerals are extracted by non Chinese companies, most are still refined or processed in China. The country dominates global refining capacity for cobalt, graphite, and rare earth elements, creating a bottleneck that the rest of the world depends on.

America’s Late Arrival

The United States is now racing to catch up. Driven by its green energy goals and strategic competition with Beijing, Washington has shifted from words to action.

In 2023, according to Johns Hopkins University’s China Africa Research Initiative, the United States overtook China as Africa’s largest foreign investor. It was the first time this had happened since 2012. The United States invested 7.8 billion dollars across Africa that year, compared with China’s 4 billion.

Most of this new investment has come through the United States International Development Finance Corporation, a government agency created specifically to counter Chinese influence in strategic regions. The corporation has already funded mining and processing projects in Rwanda, South Africa, and Namibia, and more are expected to follow.

In Rwanda, Trinity Metals received 3.9 million dollars to develop tin and tungsten mines, with refined products now shipped to processing facilities in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the United States firm ReElement Africa is building a new rare earth and battery metal refinery in South Africa’s Gauteng province, one of the first of its kind on the continent.

Africa’s Advantage and Its Caution

For the first time in decades, African nations hold real leverage. With both China and the United States competing for influence, governments are starting to demand better deals.

Economists such as Sepo Haihambo from Namibia argue that Africa must move beyond cash for ore models and instead pursue joint ventures, production sharing agreements, and local equity participation.

By insisting on local processing, skill development, and environmental safeguards, countries can turn short term exports into long term national wealth.

Zimbabwe has already banned the export of raw lithium ore. Ghana is exploring similar rules for gold and bauxite. Namibia and South Africa are both planning domestic refining projects for rare earths and battery materials.

These policies mark a turning point. Africa no longer wants to be a supplier of raw materials. It wants to be a manufacturer of value.

The New Multipolar Landscape

Although the spotlight falls on China and the United States, other nations are entering the race. India, Japan, Brazil, and South Korea are all expanding their investment footprints across Africa’s resource sector.

This diversification gives African governments more room to negotiate and greater opportunity to link mining with infrastructure, training, and industrial development.

For Africa, the question is no longer who wins between Washington and Beijing, but how the continent itself can win from their rivalry.

What Comes Next

The age of critical minerals is only beginning. Demand will triple by 2040, and whoever builds trusted, sustainable, and transparent supply chains will shape the global economy for generations.

Africa sits at the heart of that equation, not as a passive participant but as a decisive partner.

African countries with known rare earth element (REE) deposits, exploration, or production activity — based on geological surveys, mining reports, and government data as of 2025.